Dear Readers, welcome to another edition of the S.A.D newsletter — an exploration of our software, algorithms, and the data-driven world that surrounds us. Today we talk about science and pseudoscience.

Picture this: a middle-aged, white, muscular, tattooed professor from California exuding a surfer ethos, passionately discussing science and wellness on his podcast with millions of followers. His delivery is peppered with complex terms like dopaminergic neurons, grounded in science-based facts and personal development insights. So far so good?

It’s all part of the modern landscape of information overload, where science and podcasts seamlessly blend with influencer culture, promoting and endorsing pills and supplements. While empowering individuals to fix their lives and improve their understanding of science may seem noble, a recent expose (March, 25, 2024) by Kerry Howler in the New York Magazine sheds light on the slippery slope some, like Andrew Huberman (associate professor of neurobiology and ophthalmology at Stanford University), have taken into snake oil peddling.

In our fast-paced world with massive cultural and media influences, the ramifications of such practices extend far beyond individual relationships, potentially misleading and harming countless individuals. As heated discussions unfold online after the expose, The Guardian offers a nice summary:

Huberman isn’t just accused of lying to women, the piece suggests he exaggerates his relationship with Stanford. The podcaster presents himself as having a “lab” at the university, but sources suggested to New York Magazine this was a rather grandiose way of describing what could amount to little more than a postdoc working alone.

A spokesperson for Stanford meanwhile told New York Magazine: “Dr Huberman’s lab at Stanford is operational and is in the process of moving from the Department of Neurobiology to the Department of Ophthalmology.” He’s certainly an associate professor at Stanford (though he often leaves the “associate” bit when he talks about himself) but he’s not walking the halls there every day. He lives hundreds of miles away.Being a terrible boyfriend is not a crime nor does it automatically warrant a 5,000-word, cover-page piece in a magazine. Does Huberman’s personal life really matter if people find his podcast useful?

Responses to that question have been mixed. On the one hand, some people have joked that Huberman’s cheating is proof that his protocols definitely work. I mean, what normal person has the energy to date six different woman and hold down a successful career? You need superhuman levels of energy to do that. Even the women he cheated on seem to have a grudging respect for his logistical skills. “The scheduling alone!” one said. “I can barely schedule three Zooms in a day.”

But beyond Huberman’s tangled personal relationships lies a complicated issue: the manipulation of facts and the simplification of the scientific process. It's not merely a matter of personal indiscretions; it’s about fidelity to truth and the transparency to acknowledge mistakes and pitfalls. Science is about iteration and experimentation, acknowledging that it’s a journey toward understanding rather than the pursuit of ultimate truth.

Critics have long raised concerns about cherry-picked data and overreach beyond expertise, yet the allure of charismatic figures like Huberman persists. More from The Guardian:

Here’s the thing though: the piece isn’t really about Huberman’s relationship with women or his friends, it’s about Huberman’s relationship with facts. And this matters immensely: Huberman isn’t just some dude with a podcast, he has huge influence over people’s daily routines. He has over 6 million Instagram followers and more than 5 million YouTube subscribers; his podcast is one of the most listened to in the world. People try his “dopamine detoxes” to improve their concentration. They follow his advice about ways to boost their testosterone. They take the stacks of supplements he recommends. His podcast episode on what alcohol does to your brain and body (which has had over 6m views) is hugely influential in alcohol recovery circles.

He has helped mainstream a lot of wellness ideas: “How Podcaster Andrew Huberman Got America to Care About Science”, reads a Time headline from last year. He’s one of the most famous scientists in the world and he’s highly trusted at a time when trust in scientists is declining. He has also thought about parlaying that trust into politics and has said he is intrigued about running for political office one day.

But…

… the overall moral of this story isn’t that he is some monster or fraud; it is that there is no magic “protocol” to health and wellness. You just have to use your common sense: eat a balanced diet with lots of vegetables, move your body, don’t drink much, don’t smoke. You don’t need any books or influencers or Stanford professors to tell you this: it’s common sense. But common sense is boring. We all long for magic solutions. We all long for someone to help us exert control over our lives.

Indeed, this is the crux of the matter. Even though we care about science, we still want the magic solution. This phenomenon extends far beyond U.S. personalities; it’s a global trend. Silicon Valley tech magnates and even AI enthusiasts have joined the ranks of snake oil salesmen, attracted by the lucrative financial incentives, blurring the boundaries between science and sensationalism. It’s worth noting that these figures are predominantly male, though Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos fame serves as an exception, offering a semblance of gender balance.

Yuval Noah Harari is also worth mentioning here — another archetype, engaging in the propagation of populist science. Again, not everything stated by individuals like Huberman and Harari is without merit. Nevertheless, a populist aspect pervades their work, often prioritising popularity over scientific rigour. Criticisms from scholars like Darshana Narayanan (Neuroscientist and Journalist) underscore the need to question the factual validity of Harari’s narratives:

My scientific colleagues take issue with Harari as well. Biologist Hjalmar Turesson points out that Harari’s assertion that chimpanzees “hunt together and fight shoulder to shoulder against baboons, cheetahs and enemy chimpanzees” cannot be true because cheetahs and chimpanzees don’t live in the same parts of Africa. “Harari is possibly confusing cheetahs with leopards,” Turesson says.

Maybe, as details go, knowing the distinction between cheetahs and leopards is not that important. Harari is after all writing the story of humans. But his errors unfortunately extend to our species as well. In the Sapiens chapter titled “Peace in our Time,” Harari uses the example of the Waorani people of Ecuador to argue that historically, “the decline of violence is due largely to the rise of the state.” He tells us the Waorani are violent because they “live in the depths of the Amazon forest, without army, police or prisons.” It is true that the Waorani once had some of the highest homicide rates in the world, but they have lived in relative peace since the early 1970s. I spoke to Anders Smolka, a plant geneticist, who happens to have spent time with the Waorani in 2015. Smolka reported that Ecuadorian law is not enforced out in the forest, and the Waorani have no police or prisons of their own. “If spearings had still been of concern, I’m absolutely sure I would have heard about it,” he says. “I was there volunteering for an eco-tourism project, so the safety of our guests was a pretty big deal.” Here Harari uses an exceedingly weak example to justify the need for our famously racist and violent police state.

And this also holds true for recent AI hypes. Much of the AI magic we encounter is simply the work of individuals, often behind the scenes. For instance, the technology behind Just Walk Out, touted as cutting-edge AI, actually relies on the efforts of approximately 1,000 people in India.

Yet, why do we continue to fall for these - whether they’re selling actual snake oil, supplements, or AI solutions? We often forget that it is not just about the facts; it’s about the emotional and cognitive hooks these stories embed within us. Evolutionary biases and historical misconceptions play a role, as we seek simplistic narratives in a complex world. As stated in the article “What makes weird beliefs thrive? The epidemiology of pseudoscience,”:

Evolutionary theorists have distinguished between content biases and context biases acting on the dissemination of representations. Examples of context biases include the tendency of people to preferentially adopt the beliefs of prestigious individuals, known as the prestige bias (Richerson & Boyd, Citation2005). The conformist bias, by contrast, describes our inclination to accept the most commonly held representation in a community. In the history of science, the negative effects of these biases include the reign of orthodoxies, the inertia of scientific paradigms or research programs (e.g., Bowler's Citation1992 work on the Darwinian eclipse), and undue deference to the judgment of eminent scientists (Hull, Citation1990; Kuhn, Citation1962). In some instances, context biases stall the progress of science, and may take a generational shift for science to overcome. Max Planck famously quipped that science advances one funeral at a time, though others argue that this is the exception rather than the rule (e.g., Thagard, Citation1992).

The second type of transmission biases concerns the preferential adoption of beliefs on the basis of their content. Human minds are not blank slates. Biological evolution has endowed us with an intuitive conception of the world, carved around distinct ontological categories (inanimate objects, living things, agents), each coupled with respective intuitions and assumptions (Spelke & Kinzler, Citation2007). These conceptual frameworks, which are sometimes referred to as folk physics, folk biology, and folk psychology, are cross-culturally stable and probably a basic feature of our psychological makeup. Modern science, however, has not been particularly kind to this intuitive worldview. Many scientific theories run roughshod over our deepest intuitions. An indirect though reliable indicator of the growth of knowledge is that science has been demonstrably successful in overcoming many of these intuitive biases. Lewis Wolpert puts the point forcefully: “I would almost contend that if something fits with common sense it almost certainly isn't science” (Citation1992, p. 11). It is not so much that reality is always inimical to our intuitions (it's nothing personal, strictly business). It's just that, so to speak, it does not care a whit about them.

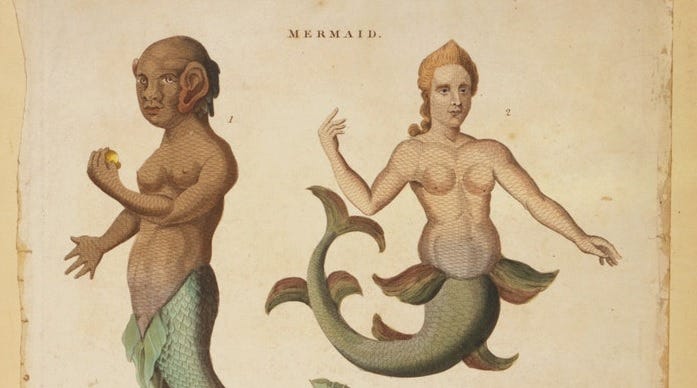

Again, the reality of science often diverges from the glamorous image portrayed in popular culture. Behind the scenes (like the Indian Guys behind the AI tools), there’s lots of tasks like data collection, tedious data wrangling, data labeling, annotations, endless writing, bureaucratic hurdles, and the constant pursuit of funding. Moreover, our perception of science is often clouded by historical narratives that romanticise scientific breakthroughs, such as Newton’s apple or Archimedes’ Eureka moment. These stories tend to oversimplify science, glossing over its intricate complexities and the multifaceted backgrounds of the figures involved. This is the gap where the snake oil salesman usually comes in and plays a role. Take Newton, for example, who delved into occult studies and alchemy alongside his scientific pursuits. Similarly, Carl Linnaeus, renowned for his contributions to taxonomy, was equally fascinated by mermaids and tritons. Such revelations remind us of the nuanced and multifarious nature of scientific inquiry, far removed from the idealised portrayals often presented to the public. And thus, it becomes easy for us to fall for the charm. We crave the science, yet we are captivated by the charisma.

Furthermore, these gaps underscore a significant void within our pursuit of scientific knowledge. As I previously discussed, we aspire to attain the metaphorical “City upon a Hill,” a symbol of enlightenment and truth. Yet, it is within these voids our search that snake oil peddlers flourish, capitalising on our vulnerabilities and offering false promises. Unfortunately, we often overlook these gaps, lacking the requisite background, time, and inclination to navigate them effectively. As consumers of science, we must acknowledge that pseudoscience permeates beyond the fringes and intersects with legitimate scientific endeavours. However, amidst our busy lives, the question arises: do we possess the time and energy required for such discernment? It’s a challenge we must confront, as we continue to witness the rise and fall of individuals akin to Huberman, whose influence persists despite their missteps. Unless structural changes occur in science education and media consumption habits, the perpetuation of misinformation and false narratives remains a looming threat.

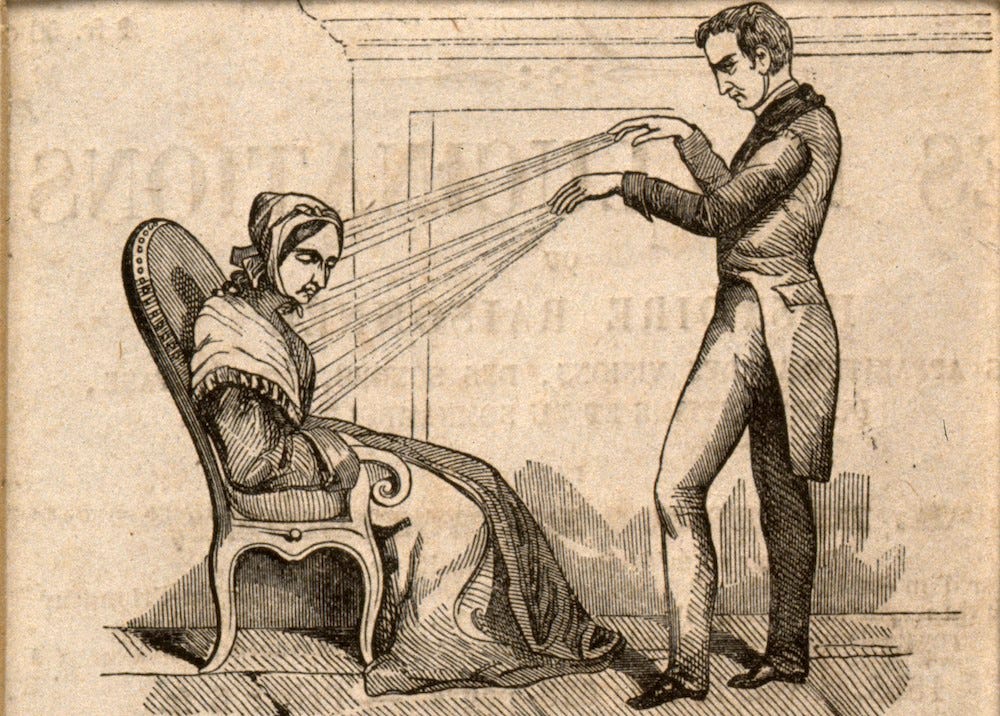

From Snake Oil to Theranos

1721 The important thing to understand about American history, wrote Mr Ibis in his leather-bund journal, is that it is fictional, a charcoal-sketched simplicity for the children, or the easily bored. For the most part it is uninspected, unimagined, unthought, a representation of the thing, and not the thing itself. It is a fine fiction …that America wa…

I will sign off with a reading tip. Michael D. Gordin's insights in his 2021 book “On the Fringe: Where Science Meets Pseudoscience” suggest that pseudoscience is a persistent force. Thus, we are compelled to adopt a nuanced understanding, recognising the complexity of the issue rather than seeking its outright eradication.