Tis the Season to Celebrate the Swedish Arms Dealer Prize

The legacy of Alfred Nobel, current data on Swedish arms export

Dear Reader,

As we celebrate 2023 Nobel prize winners, a prize that is the utmost recognition of scientific breakthroughs, literary brilliance, and peace activism — let us not forget the history behind this esteemed honour. Alfred Nobel, inventor of dynamite, the man whose name has become synonymous with peace and progress, was once branded as the “Merchant of Death.”

When Alfred’s brother passed away, a French newspaper mistakenly published an obituary for Alfred instead, with the headline: “The Merchant of Death is Dead.”

But apparently he was a “pacifist” at heart. This revelation emerges from one of his letters to Bertha Von Suttner, a novelist and a peace activist:

My factories may well put an end to war before your congresses. For in the day that two armies are capable of destroying each other in a second, all civilized nations will surely recoil before a war and dismiss their troops.

It is undeniable that the scientists, scholars, writers, and activists recognised by the Nobel Prize are truly deserving of their accolades. However, it is thought-provoking to ponder how the wellspring of peace activism has its origins in the realm of destruction.

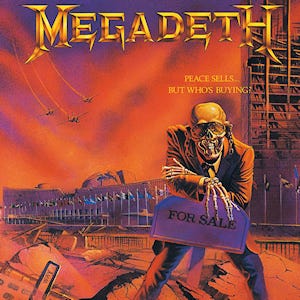

Now, let us shift our focus to the present, to the very land of Nobel’s birth—Sweden. This nation is often celebrated for its commitment to peace and diplomacy, yet beneath the veneer of neutrality lies a stark reality: Sweden is and has been a prominent player in the arms export business.

According to (ironically) Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Sweden ranks 13th among major arms exporters.

This history traces back to the 1980s and 1990s. Sweden’s so-called "neutrality" has been called into question on numerous occasions:

Swedish ‘neutrality’ is not always what it seems either. While the then prime minister, Olof Palme, was acting as UN mediator in the Iran-Iraq war, the Swedish company Bofors was sending explosives and gunpowder to Iran—almost certainly with Palme’s knowledge—via the former German Democratic Republic. During the 2000s, successive Swedish administrations condemned the conduct of the American ‘war on terror’ while collaborating in secret with CIA intelligence-gathering and ‘extraordinary rendition’. And neutrality proved no obstacle to direct Swedish military participation in the first Gulf War or the 2011 NATO-led operations in Libya.

Recent reports reveal that Sweden, despite being a major humanitarian aid donor to Yemen, has been exporting arms to the conflict-stricken region.

According to Svenska Freds, Sweden’s venerable anti-war group, says that Saudi Arabia has been buying Swedish weapons since 1998. Sweden’s main arms sales to Saudi Arabia have occurred over the past decade, while Sweden has also been selling arms to the UAE. Sweden’s arms manufacturer — Saab — opened an office in Abu Dhabi in 2017. There is no sign of a slowdown in this arms sales relationship.

In many ways, the struggles and paradoxes faced by Alfred Nobel appear to be a national trend — a delicate balancing act between creation and destruction. Thus, it seems that Nobel’s legacy is not wholly unexpected. It serves as a reminder that most countries, ironically, walk a tight line between idealism and covert arms trade. This illustrates the difficulties involved in pursuing peace in a world full of inconsistencies.