Remember the opening scene of Mad Men — a period drama about the Madison Avenue late 1950s advertising industry? Set against a backdrop of a hauntingly evocative score (RJD2’s “A Beautiful Mine”), amidst towering skyscrapers and bustling streets, Draper remains solitary, unveiling the alluring glamour that surrounds him. Yet, as he descends into his personal turmoil, the scene unravels the darker underbelly of this world. Dear reader, accompany me on a thought-provoking journey today, where I indulge in a tangential exercise reminiscent of a “Mad Men-esque” downfall.

Allow me to present an argument, albeit simplified, that unfolds as follows: Freud's nephew played a significant role in shaping the advertising, marketing, and propaganda industry, which found its platforms in newspapers, radio, television, and the Internet. With the advanced usage of algorithms, these ideas gained unprecedented scale and influence. Now, enter Large Language Models and generative AI, poised to elevate this scale and influence to unparalleled heights.

Freud’s most famous nephew (did he have another nephew? Here’s a new band name suggestion “Freud’s not so famous nephew”) Edward Bernays pushed the idea that the masses could be influenced and manipulated through the use of propaganda. Bernays also advocated engineering consent, which involved shaping public opinion to align with the goals of corporations, governments, and organisations. In a truly Freudian fashion, he believed that by appealing to people's subconscious and deep desires, it was possible to guide their decision-making processes.

Fast forward to the present, and we are witnessing the intersection of Freud's groundwork, technology, data, and AI. It is not a cliche to say that armed with an abundance of data and algorithms, advertisers have taken the art of persuasion to new heights. By leveraging insights from consumer behaviour and preferences, they aim to meticulously tailor messages that speak directly to the deepest corners of our minds.

Tim Wu's "Attention Merchants" (2016) is a work that outlines some of these historical pursuits of capturing and commodifying attention. From newspaper ads to radio, television, and online advertising, attention has always been the currency of the advertising industry.

With the advent of LLM and GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), the advertising industry is also jumping into the AI mania. Below is an example of a few such companies that are taking advantage of AI:

https://twitter.com/omneky/status/1666526520481927172

It is not just about generating texts. These generative AI models can now easily create videos that can be customised.

Let me clarify that my intention is not to criticize or pass judgment on any specific companies or their practices. The examples mentioned merely highlight potential consequences that can arise from the rapid advancement of modern AI technologies. Often, regulations and laws are established in response to emerging challenges, creating a sort of transitional phase where we currently find ourselves. I believe we do need to think carefully about how the combination of ad tech and generative AI will muddle the privacy and surveillance aspect more. Shoshana Zuboff’s work (The Age of Surveillance Capitalism) is probably the most known in this area. However, some of her and others’ argument has been labelled as Crit-Hype. See Lee Vinsel’s work to find out more.

Now, here’s where things get messy. When did you last click on a ad that you saw during your google search? I haven’t in a while. So how does ad tech work then?

Building upon Wu's work, Tim Hwang's "Subprime Attention Crisis" examines ad tech and its impact on the attention economy. As the floodgates opened to vast amounts of data, the drive for user attention became excessive and manipulative. Hwang draws parallels to the subprime mortgage crisis, suggesting that an attention bubble has formed within the advertising industry. Hwang argues that attention has become a scarce resource, with businesses competing for individuals' limited cognitive capacity. He explains how the attention economy is driven by ad tech and platforms that rely on capturing and monetising users' attention. This relentless bid for attention is similar to how the technology behind the stock market works:

Essentially, what happens is that there’s a signal that basically is put out to a marketplace saying, hey, we’ve got Tim — male, 25 to 35 — on the East Coast who’s looking at this website. Who wants to advertise to him? And essentially, there’s a number of algorithms that operate on behalf of advertisers that compete to basically bid to deliver the ad to me. And depending on which bidder wins, they upload that to my website and into my eyeballs. And this happens billions and billions of times every single day.

According to Hwang, ads worked better before but the core asset of attention has progressively deteriorated over time, rendering the advertising channel less effective and even useless (the above interview was before chatGPT came into the scene). But the ad tech industry has not collapsed, yet? Companies are still spending millions on online ads. How would the advent of generative AI introduce new possibilities for the attention merchant? As we move forward, changes are on the horizon for ad tech. The utilisation of generative AI can potentially reshape the way attention is captured. This technology has the potential on the one hand to create more engaging and personalised advertisements, tailored to the individual preferences and interests of users and on the other hand unprecedented scale of surveillance and privacy violation. By leveraging generative AI, the attention merchant will find new avenues to recapture attention.

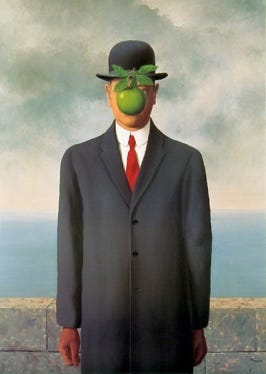

I end this exercise with some name-dropping of French philosophers. It won’t sound important until I quote one of those French ones. But this one might be onto something. I am talking about Jean Baudrillard's hyperreality and simulation.

For a French philosopher, his basic idea is not that complicated. His theory, in its essence, explores how the postmodern world generates a simulated existence devoid of true representation. He uses the example of Disneyland (Simulacra and simulation, 1994, page 12) to make his point:

Disneyland is there to conceal the fact that it is the “real” country, all of “real” America, which is Disneyland (just as prisons are there to conceal the fact that it is the social in its entirety, in its banal omnipresence, which is carceral). Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, when in fact all of Los Angeles and the America surrounding it are no longer real, but of the order of the hyperreal and of simulation. It is no longer a question of a false representation of reality (ideology), but of concealing the fact that the real is no longer real, and thus of saving the reality principle.

I will leave you with these words to think about advertising and generative AI. In a sense, advertising already embodies a hyperreal simulacrum that bears no genuine connection to reality. Yet, we are now poised on the precipice of what could be considered the fifth stage of simulation. According to Baudrillard, the journey through hyperreal reproduction comprises four distinct steps: a) the rudimentary reflection of reality in immediate perception, b) the distortion of reality in representation, c) the fabrication of reality in pretense, and finally, d) the emergence of the simulacrum, an entity entirely divorced from any conceivable reality. What should we call this 5th stage? Transcendent Simulacrum? Oh, another band name!

That is all for today. Stay tuned, I am working on another interesting issue on “Hallucination and AI”.

NB: Before we conclude, let's take another detour into the realm of peculiar band names. If, by some serendipitous turn of events, a band called "Freud's Not So Famous Nephew" comes into existence, kindly ensure that my royalty check finds its way to me. On a similar note, I recently stumbled upon another quirkily intriguing name attributed to the founder of the band Silver Jews (a musical gem worth exploring). David Berman had a whimsical desire to name a band called "Trad Arr". Just imagine the level of hyperreality that would unfold within the CD liner notes adorned with such a name!