Contemplating Chile. I recently read Roberto Bolaño’s "Distant Star," a novel that delves into the exploits of an “aviator poet” who manipulates the backdrop of the 1973 Chilean coup d'état to create his rendition of the New Chilean art — “a multimedia venture entailing skywriting, torture, photography, murder, and verse”.

This particular period of Chilean history (1971-1973 and onwards) has been back in the news now, as it has been fifty years since the fateful date of September 11, 1973, the day when General Augusto Pinochet led the Chilean coup.

I wish the narrative and discussions were as wildly multifaceted as Bolaño’s because the history definitely is. However, the portrayal of Latin American political history is overshadowed by the Cold War ideological battles, but it possesses a unique tapestry of history, ideology, and violence. Undeniably, the involvement and influence of the USA and the USSR are significant, yet the nuanced local and regional dimensions are frequently overlooked in the big narrative.

Telecommunications and computer technology played a huge role in the turbulent history of Chile. Often, we underestimate these factors, reducing technology, especially software and data, to depoliticised realms of mere numbers and jargon, reserved for the tech-savvy. However, a closer examination of Chile's historical narrative, entwined with economic transformations and political turbulence, uncovers the significant role played by “computers.” It becomes evident that the trajectory of the modern computing industry might have embarked on an entirely different course had it not been for the Pinochet coup. This historical journey also serves as a cautionary tale against simplistic "techno solutionism."

In the September 2nd (2023) edition of The Economist , the following was highlighted:

Elected in 1970, Allende had proclaimed “the Chilean road to socialism”, an attempt to carry out a revolution by peaceful parliamentary means. But his Popular Unity (Unidad Popular or up) coalition lacked a congressional majority. It polarised Chile and plunged it into chaos. Many Chileans, and a majority of politicians, welcomed the coup, imagining that the army would restore order and call a fresh election.

Two things turned Allende into a martyr for democracy as well as a global icon for the left. One was the brutality of the coup and its aftermath. Pinochet’s junta murdered 2,130 people and tortured at least 30,000, many cruelly, according to investigations under later democratic governments. The second was Allende’s defiant final speech to the nation, broadcast from La Moneda at 9.10am. It lasted less than seven minutes, his voice calm and measured even amid shouting in the background. “I will not resign,” he declared. “I will repay the loyalty of the people with my life... Always remember that much sooner than later the great avenues along which free men pass to build a better society will once again be open.”

In the realm of economic reform, Chile after Allende became the lab for the “Chicago Boys”. From The Economist again:

Pinochet’s economic policy was another shock. Most Latin American armies believed in state-led industrialisation. But Pinochet was persuaded to hire the “Chicago boys”, a group of young technocrats trained at that city’s university under an exchange programme run by Chile’s Catholic University. They were free-marketeers, disciples of Milton Friedman. They tore down tariff barriers and controls and privatised everything except the copper industry (the revenues of which went partly to the army). They made mistakes: a fixed and overvalued exchange rate and rampant insider lending by financial conglomerates crashed the economy in 1982. It recovered under more pragmatic management.

This persuasion had U.S. involvement (the Nixon government at that time) and was influenced by the Cold War atmosphere. However, before the “Chicago Boys” there were the “Santiago Boys” and the Cybersyn project, where “software” and “data” played a significant role. Most coverage of the Chilean coup, Allende, and Pinochet fails to mention this large-scale technical project. A podcast by Evgeny Morozov, released in July 2023, recounts the complex and bewildering story of the “socialist computing utopia” that Allende attempted to build and puts the techies at the centre of the narrative. It's a fascinating tale of building cybernetics systems, political conspiracy, international espionage, and political manoeuvring involving diverse stakeholders, including the CIA. The story also introduces a British management executive who transformed into a bearded, poetry-writing hippie after the fall of Allende. The release of the podcast is getting plenty of media coverage. However, Morozov has been accused of plagiarising a New Yorker article in 2014 and not attributing properly the pioniering work of Eden Medina .

The roots of Cybersyn (“cybernetics” + “synergy”) are, of course, influenced by Norbert Wiener's original concept of Cybernetics (1948) emerged in the the early days of modern computing. This idea initially focused on the behaviour of dynamical systems with inputs and how feedback modifies their behaviour and later has been extended to artificial neural network and modern development of the Internet. The Chilean attempt of this is Cybersyn which can be summarised as follows: Developed with the assistance of the British management guru Stafford Beer, it consisted of a network of telex machines (“Cybernet”) in state-run enterprises for transmitting and receiving information with the government in Santiago. Information from the field would be fed into statistical modeling software (“Cyberstride”). However, following the military coup in 1973 that ousted Allende, the project was dismantled, and its full potential was never realised.

One of the unique aspects of the Cybersyn project, influenced was its emphasis on “real-time” data. Unlike traditional Soviet-style central planning, which often relied on static and periodic data, Cybersyn aimed to collect and process data in real time. This meant that the system continuously monitored and analysed economic and industrial data as it was generated, providing decision-makers with up-to-the-minute information. According to the Wikipedia:

The Cybersyn system was put to good use in October 1972 when about 40,000 truck drivers went on strike action. Due to the network of telex machines in factories across Chile, the government of Salvador Allende could rely on real-time data and respond to the changing strike situation. Gustavo Silva, the executive secretary of energy in CORFO at the time, mentioned that the system's telex machines helped organize the transport of resources into the city with only about 200 trucks driven by strike-breakers, thus lessening the potential damage caused by the 40,000 striking truck drivers.

Scholars have also paid significant attention to the design aesthetics of the Cybersyn project, particularly the Opsrooms which aimed to create an “Environment for Decision”. The design team was lead by german designer Gui Bonsiepe whose work influenced modern design thinking for technology interfaces. The Opsroom featured swivel chairs with buttons designed to control large screens for data projection and other panels displaying status information. The chairs even included ashtrays to accommodate the Cuban cigar enthusiast Stafford Beer. Gui was part of the German Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm.

The United States had interests in Chile’s internal politics for a long time, primarily aimed at preventing Chile from becoming another Cuba. Following the successful coup in Brazil (1964), the Nixon government devised an elaborate plan to undermine and sabotage Salvador Allende's presidency. A conglomerate style company called ITT Inc. (founded in 1920 as International Telephone & Telegraph) played a significant role in this effort, as it had substantial interests in the technological development initiated by Allende's government. ITT, whose Chilean holding, Chiltelco, Allende had nationalised the telecommunication industry upon assuming the presidency, actively fostered anti-Allende sentiment and provided funding to opponents of his government in the lead-up to the coup d'état. They proposed an “economic squeeze” on Chile, including denial of international credit, bans on imports of Chilean products. Similar to telecommunication, the copper industry also went through similar nationalisation effort. Therefore, the control over the region and the politics strongly related to topic of controlling resources and commodities as well.

ITT was involved in telecom, aerospace, transportation, energy, industrial markets, industrial processing, motion technologies. Harold Geneen, a prominent advocate of corporate conglomerates, was associated with ITT during Allende’s time. ITT had a history of reactionary politics, dating back to its collaboration with Nazi Germany during World War II. ITT typically received generous compensation. Geneen's anti-communist stance deepened after Fidel Castro's nationalisation of Cuba's telephone system without compensation in 1961 (see classified documents released by the CIA). And the conglomerates is still active worldwide, including Chile. One of the companies related to ITT now supplies “Heavy Duty Slurry Pump” to copper mines in Chile and their webpage has the following description:

ITT is a diversified leading manufacturer of highly engineered critical components and customised technology solutions for the energy, transportation and industrial markets. Building on its heritage of innovation, ITT partners with its customers to deliver enduring solutions to the key industries that underpin our modern way of life. ITT is headquartered in Stamford, Connecticut, with employees in more than 35 countries and sales in approximately 125 countries.

Shouldn’t they add something about their involvement in Chile’s 9/11? At least a link to the CIA page entitled: “ITT PLEDGED MILLIONS TO STOP ALLENDE”?

So why does this history matter after a half a century ?

If Salvador Allende had remained as president and the Cybersyn project continued to evolve, it could have had a significant influence on the development of the modern internet, even though it lacked the technological sophistication of ARPANET. Cybersyn's emphasis on decentralised decision-making and real-time data exchange could have served as an early model for a more decentralized and democratic internet. Instead of a top-down structure, the internet might have evolved to prioritize peer-to-peer communication and collaboration. The Cybersyn project aimed to empower workers and factory managers by providing them with real-time data. Similarly, the internet could have been designed to prioritise user empowerment and control over personal data, potentially mitigating some of the privacy concerns we see today. Cybersyn demonstrated the potential for combining technology with social innovation. This could have encouraged more extensive exploration of how technology could address social challenges. The history also shows role of the state in shaping technology for societal benefit rather than mere efficiency or profit. It also points out the value of older technologies and the need to think holistically in terms of systems rather than relying solely on technological solutions.

Eden Medina’s book goes into more details on this topic and the implications:

This story of technological innovation also challenges the assumption that innovation results from private-sector competition in an open marketplace. Disconnection from the global marketplace, as occurred in Chile, can also lead to technological innovation and even make it a necessity. This history has shown that the state, as well as the private sector, can support innovation. The history of technology also backs this finding; for example, in the United States the state played a central role in funding high-risk research in important areas such as computing and aviation. However, this lesson is often forgotten. […]

The history of Project Cybersyn is, moreover, a reminder that technologies and technological ideas do not have a single point of origin. Ideas and artifacts travel and can come together in different ways depending on the political, economic, and geographical context. These unique unions can result in different starting points for similar technological ideas. For example, this history has suggested an alternative starting point for the use of computers in national communication and data-sharing networks. However, not all these technological starting points lead somewhere. What leads to the success of one technology and the demise of another cannot always be reduced to technological superiority. Ultimately, Cybersyn could not survive because it was tied to a political project that, in the context of the cold war, was not allowed to survive. As Project Cybersyn illustrates, geopolitics can affect which technologies fall by the wayside. Simply put, international geopolitics is an important part of the explanation of technological change, especially in nations that served as ideological battlegrounds during the cold war.

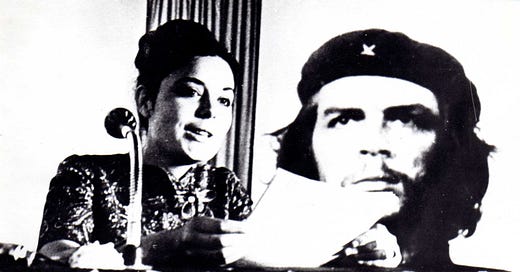

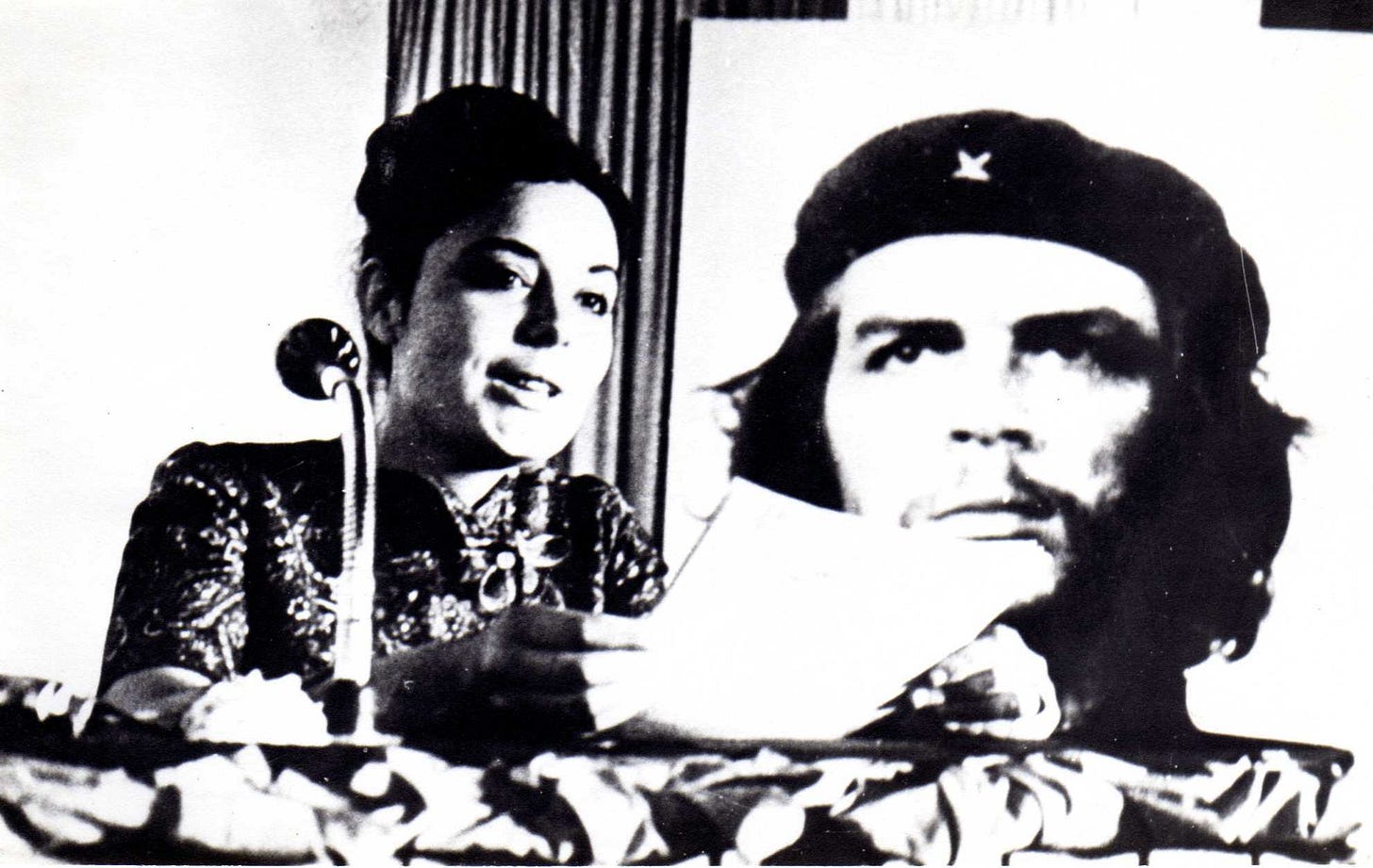

Final note, besides the boys, there another fascinating figure that needs extra attention. One of Allende’s daughter — Beatriz Allende. Beatriz Allende was not only a witness to the tumultuous political history of Chile but also an active participant in the struggle for social justice.