Analog 2.0

Materiality, Luddism and thinking about the post-digital world

I am coining a new term. You heard it here first: Analog 2.0 #analogtwopointoh.

Analog 2.0 allows us to pause and think about the physical and the material aspects of our digital world. This is not a binary framework of digital vs. analog. Nor it is an anti-digital/anti-technology stance. Analog 2.0 is a way to appreciate, investigate, and understand the physical and at the same time, think about the logic, complexity, and power behind the digital. Analog 2.0 refers to a growing trend of needing and appreciating curated digital and physical objects, finding a way to co-exist in both the analog and the digital world.

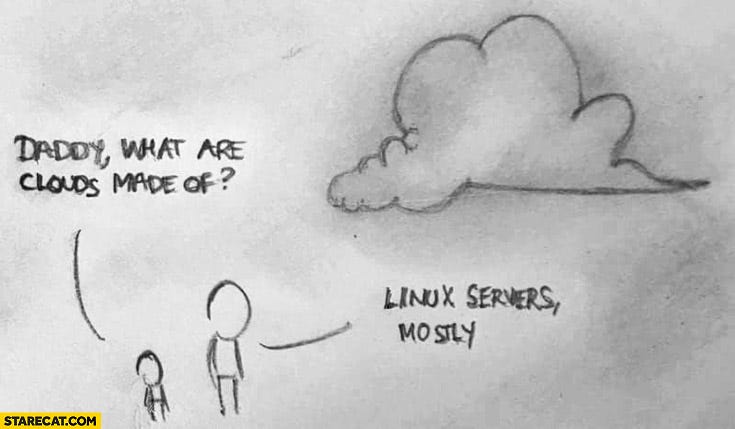

We never really think about the software and the data that we use daily stored out there in the cloud as material things. However, there are complex, enormous logistic material aspects associated with the “immaterial” cloud:

The history of technological development is also the history of capital and energy flows. Just like the railroads and industrialization, digital infrastructure requires extensive resources in terms of building materials and labour, let alone energy. Digital technology also promotes the exchange of raw materials for profit.

In the scholarly discussions, materiality is not just about the physical aspect but also about having relevance or significance — thinking about “what matters”. But before we get too scholary, let me sing the praise for the analog starting with the humble Post-It notes. A recent article by Clive Thompson, points out how Post-It notes are possibly the best designed “tool for thought”.

These colourful notes provide a certain sense of materiality that you cannot get with the software. I have used Post-It at work but then took the physical notes to create user stories and tickets in github. Then came back to my desk with pen and paper to draw things. To me that is Analog 2.0.

Similarly, we all have read about the revival of vinyl records despite the popularity of various streaming services. More and more we are noticing the “mainstream” approach of the music recommendation systems (with full disclosure here, I use a streaming service, I do not own a record player but do still occasionally buy CDs and still listen to the radio). The algorithm is getting bored and boring. There are newsletters like Flow State that provides curated recommendations that are becoming popular. And this is not just about music — the idea of community curated knowledge to sort through the gazzillion data is gaining traction.

Even though there are other pressing problems to worry about in this world, have you thought of what will happen to your music stored in the streaming services after 20 years?

Unfortunately, the experts on media preservation and the music industry whom I consulted told me that I have good reason to fear ongoing instability. “You’re screwed,” said Brewster Kahle, the founder of the Internet Archive, after I asked him if I could count on having my music library decades from now.

The reason I’m screwed is that Spotify listeners’ ability to access their collection in the far-out future will be contingent on the company maintaining its software, renewing its agreements with rights holders, and, well, not going out of business when something else inevitably supplants the current paradigm of music listening. (Kahle sees parallel preservation problems with other forms of digital media that exist on corporate platforms, such as ebooks and streaming-only movies.)

How information is digitally stored matters. Where and who stores it matters (on a side note, see this article about the importance of storing documents in plain text format).

Vinyl demonstrates the ways material objects play a significant role in our everyday lives. Similar to Vinyl, physical cookbooks are also seeing some revival (see this funny rant about “Why it's so maddeningly frustrating to read recipes online”). The analog devices provide methods of control and freedom even though it does not provide speed. We can use both analog and digital and get the job done, maybe a bit slower. But maybe it is time to ask, do we need things to be always fast?

There is a growing trend that is seeking out “Slowness” such as the slow tech movement and the slow media manifesto inspired by the Slow Movement Culture. These movements can be summarized via a notion called “post-digital”, where consumers and activists envision how to escape the “omnipresence of the digital”. These ideas also go back to the1960s counter culture narrative:

In “What is ‘post-digital’?”, writer and artist Florian Cramer explains that post-digital culture is concerned with addressing this sense of alienation by focusing on what it is to be human, with particular reference to our rapidly changing relationship with information technology. Cramer suggests that the Fluxus movement of the 1960s, in which artist’s books were produced to be “auratic, collectible objects”, resembles post-digital culture today (Cramer 2012). He goes on to say that we are at a similar historical point, “where electronic books […] are eclipsing print” which has resulted in a renaissance of artist bookmaking which “emphasises, if not fetishizes, the analog, tangible, material qualities of the paper object” (Cramer 2012).

Again, the idea is not to get rid of the streaming services or go off the grid. It is to slow down and appreciate the physicality and think about the processes and logic behind our digital world.

We should use and embrace the change and technological development like the Luddites, who were a secret organisation of workers in the 19th century. The term has a negative connotation used for someone that is anti-technology or not good at using and embracing technology. But that is a misunderstanding of the Luddite movement. Jathan Sadowski explains how Luddism provides a powerful framework for critique and why we all should be Luddites. This bodes well with my Analog 2.0 idea:

A neo-Luddite movement would understand no technology is sacred in itself, but is only worthwhile insofar as it benefits society. It would confront the harms done by digital capitalism and seek to address them by giving people more power over the technological systems that structure their lives.

This is what it means to be a Luddite today. Two centuries ago, Luddism was a rallying call used by the working class to build solidarity in the battle for their livelihoods and autonomy.

The power behind Analog 2.0 is that it is an articulation of our relationship with what matters. This can be extended to different ways of looking at our digital and post-digital world. Let’s slow down, write a few lines with pen and paper, pick up a book before you send that email.

We evolved as a species in a physical and material world, and anything analog fits our evolution. Analog 2.0 immediately struck a nice chord with me. I had a nice collection of LP vinyl records but one of my sons wanted half of them and I gladly bequeathed them to him. Some Japanese exchange students visiting my home in Indiana were fascinated with my turntable (and it was vintage Japanese). I’ve seen a revival in using simple brick facades in mid-rise buildings in America and I have to think it is because of the warm and human scale of bricks. Digital often is like consuming empty calories, but material things are as old as the planet.

Luddites were a sect of weavers who feared displacement of their labor by automated looms. Analog 2.0 is deeper and more complex than this!